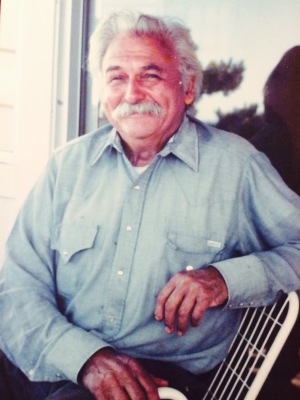

E. FRANKLIN PEACE 1926-2015

E. Franklin Peace, a longtime Big Sur beekeeper and direct descendant of the area’s early pioneers, died in his sleep on May 31. He was 89.

Mr. Peace’s great great-grandfather was William Brainard Post, for whom the Post Ranch is named, who left Connecticut to settle in Big Sur in the 1850’s. Post married Anselma Onesimo, a Native American woman of Rumsien Ohlone (Coastanoan) descent whose ancestors helped Junípero Serra build the Carmel Mission. Mr. Peace’s grandfather was Edward Grimes, another 19th century ranching family on the coast, that emigrated from England.

For nearly 70 years, Mr. Peace kept more than one hundred hives in the Garrapata and Palo Colorado Canyon areas of Big Sur, as well as in the nuns’ garden at the Carmelite Monastery. He produced up to three tons of honey a year, and made deliveries to Big Sur grocery stores, restaurants and residents in his rambling pickup truck.

A lifelong Monterey County resident, Mr. Peace was born in the Monterey Hospital in 1926, and joined the U.S. Navy the day after graduating from Monterey High School. He served in Guam from 1944-1946.

His passion for bees began at age 14, when his father caught a swarm in their Pacific Grove backyard. Father and son bought a wooden box hive for the colony, which quickly expanded to five hives, until his mother put her foot down. They relocated the bees to a cousin’s ranch in Big Sur, but not before leaving one hive on the front porch of the house next door. Their neighbors, who were Japanese, were taken to World War II internment camps and Mr. Peace and his father used the bees to successfully protect the home until their friends returned.

After the war, Mr. Peace bought a decommissioned Army bus from the Fort Ord military base and renovated it into a portable honey rig; tearing out all the seats and installing a honey spinner so he could extract and bottle honey in the fields next to his Big Sur apiaries.

In his teens and early twenties, Mr. Peace also worked as a sardine fisherman on Cannery Row, using a skiff boat to haul in nets of fish. He also worked inside the canneries, rolling large steel crates of canned sardines into a steam cooker to seal the tins.

When the sardine population began declining in the mid-fifties, Mr. Peace relocated to Big Sur to apprentice under builders Frank and Walter Trotter. For the next eight years, the brothers taught Mr. Peace ranching, construction and plumbing. Mr. Peace became a well-known plumber in Big Sur, once climbing the steep Santa Lucia Mountains to build a gravity-fed water system that directed water from a natural spring to Nepenthe restaurant.

When he was 37, Mr. Peace met a schoolteacher he fancied while square dancing. Two years later, during a hoedown in Nevada, Mr. Peace and Ruth Miller dashed out to a courthouse to get married, asking a stranger in the building to serve as their witness. They settled in Carmel Valley, where he lived ever since.

Mr. Peace was a well-known storyteller and patient teacher who mentored many people in the beekeeping profession. He once summed up his love of beekeeping:

“I’m social. I like to talk. The best thing is talking to people about bees. People want to know if I’m having a good year, how many pounds of honey. People don’t know a lot about bees, but they are very curious. I tell them I have to take care of the bees and put them in a place where they can fly free.”

Mr. Peace is survived by his wife, Ruth; sister Ellanah Plain of Concord; step-son Stephen Rial of North Fork, step-daughter Sally May of Carmel Valley; five step-grandchildren: beekeeper Meredith May (and this blogger) of San Francisco, Matthew May of San Mateo, Shelley Billante of Las Vegas, Wendy Wallace of North Fork, and Jessica Hansen of North Fork; and nephew Craig Plain of Concord; and niece Cindy Terry of Danville.

No immediate memorial services are planned.

Donations in his name may be sent to the Big Sur Historical Society, P.O. Box 176, Big Sur, CA, 93920; or to the Carmel Valley Library, 65 W. Carmel Valley Rd., Carmel Valley, CA 93924.